恩地孝四郎ONCHI Koshiro

明治末から大正初期の美術界では、渡欧者や出版物を介して同時代の海外動向が紹介され、これまでの慣例に捉われない革新的な表現への熱狂が生まれました。とりわけ声高に叫ばれたのは、自己表現における絶対的自由や個性の表明でした。この機運はとくに絵画分野に強く、少なからぬ作家たちが、ゴッホやマチスらの造形様式に感化されながら自己表現の可能性を探り始めました。

こうした「革新性」を希求する流れは、同じ平面表現に類する版画にも起こり、単なる複製技術から、再び創作性を取り戻そうとする「創作版画」運動に繋がります(※1)。恩地孝四郎(おんち・こうしろう 1891-1955)は、この系譜に連なる作家として、さらに日本における抽象表現の先駆者として知られています。

恩地孝四郎は、東京区裁判所検事を務める父・轍の四男として生まれました。父の希望で医者を志し、獨逸学協会学校中学校に進学するも第一高等学校(旧制)受験に失敗。浪人生として過ごしていた1909(明治42)年12月に、竹久夢二(たけひさ・ゆめじ 1884-1934)の著書『夢二画集 春の巻』(洛陽堂)を目にします。恩地はすぐさま読後感を送り、これをきっかけに竹久夢二への私淑が始まりました。医学の道へは進まず、東京美術学校西洋画科予備科に入学しますが、「夢二学校」と当時を振り返るほど熱心に通ったのは、夢二のもとでした(※2)。そしてここで交友を結んだ同世代の田中恭吉(たなか・きょうきち 1892-1915)、藤森静雄(ふじもり・しずお 1891-1943)とともに、版画制作を始めます。彼等もまた画学生としてアカデミックな教育を受けていましたが、旧態依然とした指導に飽き足らず、実験的な創作手段として木版画に打ち込みました。

彼ら3人による版画雑誌『月映』(つくはえ)は、手摺りの私家本(私輯『月映』)と機械摺りの公刊本が残されています。私家本は1914(大正3)年4月から同年7月までの短期間に6輯が編まれ、公刊本は同年11月から翌年11月まで刊行されました。夜や闇を想起させる退廃的なイメージ、やせ細った人体をゴッホ風のうねる線刻がまとわりつくなど、どこまでも感傷的で死の予感すら漂います。生死のモチーフを3人が共有していたのは、親しい友人や肉親の死、田中の身体が流行り病(結核)に侵されていたことなど、現実世界の逼迫した状況がありました。私家本の制作自体も、病床の田中を案じて準備を急ぐ意図がありました。

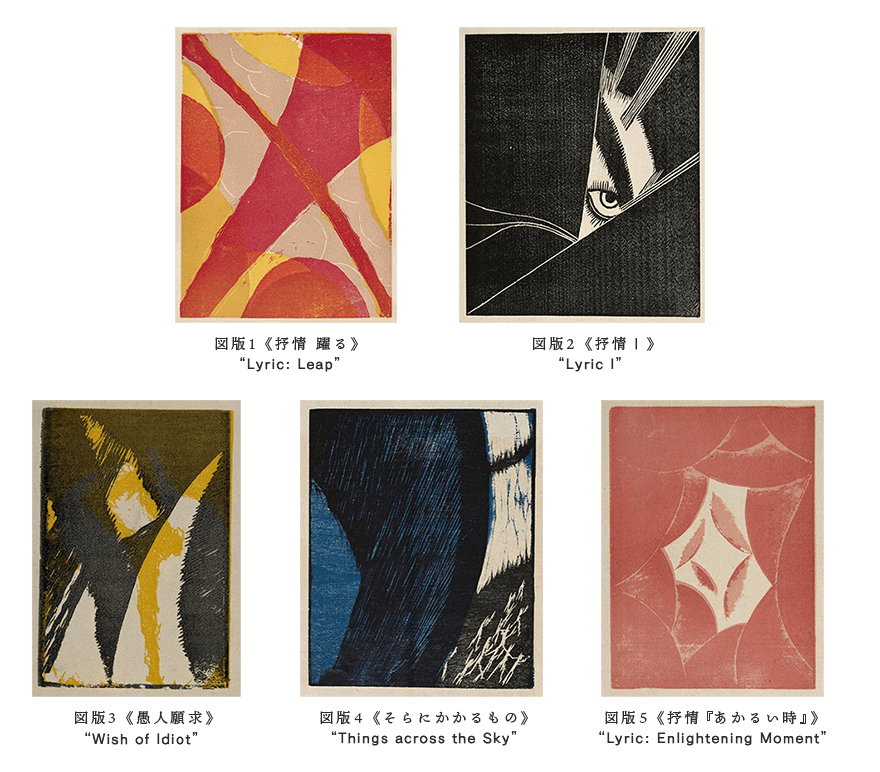

田中や藤森が、頼りなげに細長くデフォルメされた人体や光・影のモチーフを、その負のイメージに抗うごとく荒々しく彫り刻む一方で、恩地の表現には、それよりも静的かつ図形的なアプローチが見られます。公刊『月映』Ⅰ所収の《抒情Ⅰ》(図版2)は、これに先立つこと4か月前に《泪》というタイトルで制作され、すでに私輯『月映』Ⅲに収められています。大きな眼が、睨み据えるように視線を向ける本作。「目」という具体的なモチーフが登場していますが、白線が横断することで生まれる画面分割、右上部にみられる光線のような白線の束など、図形的モチーフへの関心がうかがい知れます。《愚人願求》(図版3)や《そらにかかるもの》(図版4)では、そのタイトルから僅かに具象的なモチーフを推定できる程度となり、見る者の単純な解釈を拒むかのように、イメージが恩地の意識深くに固着したまま表現されています。さらに日本初の抽象作品と評される《抒情『あかるい時』》(図版5)や「抒情シリーズ」の連作が生まれ、僅か10㎝四方の紙上に、緩やかな円弧と多角形、反響し合うような色彩の諧調が織りなす空間を表出させました。恩地はその後も、版画のみならずペン画、油彩画、装幀と表現媒体を変えながら、心象の現出、静物や器物といったモチーフの視覚的再構築を試みました。

ところで公刊『月映』は、資金回収が困難だったために、第7輯を「告別」と題して終刊しますが、田中は無念にも終刊日を待たずしてこの世を去りました。すでに述べたように、『月映』編集当時は、3人それぞれが兄妹や仲間との死別に直面しており、作品にはその死を追惜する意識が垣間見えます。道半ばながらも田中が自らの生命を『月映』に燃やし尽くし、藤森と恩地はその喪失感を乗り越えて自らの創作を深化していきました。

『月映』刊行から100年余りが経ちました。相変わらず私たちの生命は、想定外の災害や微細なウイルスの侵襲によって、いとも簡単に失われてしまう存在です。芸術に病を治癒する力はなく、「抒情」や「感傷」という言葉はいかにも頼りなく響きます。しかし悲劇を深く内観することで、他ならない自分自身を再び強く勇み立たせ、歩み進めることができるのだと、彼らの作品が語りかけてくるようです。

東北福祉大学芹沢銈介美術工芸館 学芸員 今野咲

翻訳:メイボン尚子(WAGON)

(※1)伝統的な木版画は分業制作でしたが、創作版画(運動)では、全ての工程を個人が行なうこと(自画・自刻・自摺)で、芸術性の向上を目指しました。山本鼎(やまもと・かなえ 1882-1946)が雑誌『明星』で発表した《漁夫》(1904)は、この運動の嚆矢として知られます。のちに続く作家たちは、カンディンスキーといったドイツ表現主義の影響を受けており、恩地も1914年3月に日比谷美術館で作品を観覧しています。

(※2)夢二デザインの小物雑貨を取り扱う「港屋絵草紙店」は、田中恭吉が病状悪化で帰郷するまで、3人の活動拠点になっていました。後述する版画雑誌『月映』は、夢二の著書を出版する洛陽堂から公刊されており、その背景には夢二の手助けがあったものと考えられています。

[参考]

・『竹久夢二とその周辺』宮城県美術館・和歌山県立近代美術館 1988年

・『月映』NHKプラネット近畿 2014年

・『恩地孝四郎展』東京国立近代美術館・和歌山県立近代美術館 2016年

[画像]

すべて愛知県美術館所蔵。公式サイトで公開されているパブリック・ドメイン画像を転載している。

図版1 恩地孝四郎《抒情 躍る》1915年 木版、紙 13.4×9.8㎝(1915年5月5日発行『月映』Ⅵ所収)

図版2 恩地孝四郎《抒情Ⅰ》1914年 木版、紙 13.3×11.0㎝(1914年9月18日発行『月映』Ⅰ所収)

図版3 恩地孝四郎《愚人願求》1914年 木版、紙 8.6×5.8㎝(1914年12月16日発行『月映』Ⅲ所収)

図版4 恩地孝四郎《そらにかかるもの》1914年 木版、紙 13.6×11.0㎝(1914年12月16日発行『月映』Ⅲ所収)

図版5 恩地孝四郎《抒情『あかるい時』》1915年 木版、紙 13.5×9.6㎝ (1915年3月7日発行『月映』Ⅴ所収)

In the Japanese art world from the end of the Meiji era to the beginning of the Taisho era, contemporary overseas trends were introduced through either people who had visited Europe or publications from Europe, and an enthusiasm towards innovative expression that is not restricted by traditional rules or style emerged. In particular, what arose was a manifestation of the absolute freedom and individuality in self-expression. This tendency was notably strong in the field of painting, where a number of artists, inspired by the style of Van Gogh and Matisse, began to explore the possibilities of their own expression.

This desire for innovation also occurred in the field of printmaking, another two-dimensional artistic form, and led to the “Sosaku-hanga (creative prints)” movement, which sought to reclaim creativity in printmaking from mere reproduction techniques (*1). ONCHI Koshiro (1891-1955) is known as an artist in this lineage, and also as a pioneer of abstract expression in Japan.

ONCHI Koshiro was born as the fourth son of his father, Wadachi, a prosecutor at the Tokyo District Court. As per his father’s wish, Koshiro tried to become a medical doctor and entered Doitsugaku Kyokai Junior High School (School of the Society for German Studies), but failed the entrance examination for Daiichi High School (one of the first high schools in Japan under the prewar education system). In December 1909, while studying for another year’s high school entrance exam, Koshiro came across a book by TAKEHISA Yumeji (1884-1934) entitled “A Collection of Works by Yumeji: Spring” (Rakuyodo). ONCHI immediately sent Yumeji a letter expressing how he found the book. This was the start of his personal admiration towards TAKEHISA Yumeji. Koshiro did not go on to study medicine, and enrolled in the preparatory course in the Western Painting Department at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. Yet, instead of this formal educational environment, it was at Yumeji’s, which Koshiro attended with such enthusiasm that he later called it “Yumeji School” (*2), that he began to make prints with his contemporaries TANAKA Kyokichi (1892-1915) and FUJIMORI Shizuo (1891-1943), with whom he initiated friendships. They too were attending an academic education as art students, but, as they weren’t really satisfied with the old-fashioned ways of teaching, they threw themselves into woodblock printing as a means of experimental creation.

The print magazine “Tsukuhae”, established by these three artists, survives today in two versions: a hand-printed private edition and a machine-printed public edition. Six private editions were published in a short period of time between April 1914 and July 1914, and the public edition was published from November 1914 to November 1915. The decadent imagery evokes night and darkness, and the Van Gogh-like undulating line engravings cling to the emaciated human body: always there was a sense of sentimentality and even death. The motifs of life and death, shared by all three artists, reflected the pressing circumstances of the real world: the death of close friends and relatives, and the fact that TANAKA’s body was affected by an epidemic (tuberculosis). The production of the private book itself was intended to be a hurried preparation for TANAKA, who was ill.

While TANAKA and FUJIMORI carve unreliably long and thin deformed motifs of human body and light and shadow in a rough way, as if they are resisting the negative image, ONCHI’s expression has a more static and graphic approach. “Lyric I” (Image 2), featured in the public edition of “Tsukuhae” I, was produced four months earlier under the title “Tears” and was already included in the private edition of “Tsukuhae” III. In this work, a large eye glares fiercely at the viewer. Despite the specific motif of the eye, the division of the picture by the crossing of the white lines and the group of white ray-like lines in the upper right also tell the artist’s interest in graphic motifs.

In the works “Wish of Idiot” (Image 3) and “Things across the Sky” (Image 4), the titles give only the slightest hint that the motifs can be something figurative, but the images represented remain deeply embedded in ONCHI’s consciousness, as if they defy the viewer’s simple interpretation. In addition, Koshiro produced “Lyric: Enlightening Moment” (Image 5), which has been considered as the first abstract artwork in Japan, and “Lyric” series, in which the gradual arcs, polygons and the echoing tones of colours are woven together to create a space on a mere 10cm square of paper. In the following years, ONCHI attempted a manifestation of mental images, and a visual reconstruction of motifs such as still lifes and vessels, by changing the medium of his creation from prints to pen-and-ink drawings, oil paintings and book cover design.

The public edition of “Tsukuhae” ended with the seventh edition entitled “Farewell” as it was not economically sustainable. But TANAKA sadly passed away before the final issue was published. As mentioned, at the time of editing the “Tsukuhae” magazine, each of the three artists was facing the bereavement of siblings and friends, and there are glimpses of a sense of sorrow for their deaths in their works. TANAKA devoted his life to “Tsukuhae”, while FUJIMORI and ONCHI overcame their loss and deepened their own creativities.

More than 100 years have passed since the first publication of “Tsukuhae”. As ever, our lives are easily lost to unexpected disasters or to minute virus invasions. Art has no power to cure illness, and the words “lyricism” and “sentimentality” sound not practically useful. But their work seems to tell us that, through a deep introspection of tragedy, we are able to regain our strength and the courage to go on.

KONNO Saki

Curator

Tohoku Fukushi University Serizawa Keisuke Art and Craft Museum

Translation :Naoko Mabon (WAGON)

(*1) Traditional woodblock prints were created by several people across divided production stages, but the “Sosaku-hanga (creative prints)” movement aimed to improve the artistic quality of the prints by having an individual carry out the entire production process themselves (self-drawing, self-carving, self-printing). The “Fisherman” (1904), published in the “Myojo” magazine by YAMAMOTO Kanae (1882-1946), is known as a pioneer of this movement. Subsequent artists were influenced by German Expressionism, such as Kandinsky, whose work ONCHI also saw at the Hibiya Art Gallery in March 1914.

(*2) The “Minatoya”, a shop selling small goods designed by Yumeji, was the base of activities for the three artists until TANAKA Kyokichi returned home due to his deteriorating health. The print magazine “Tsukuhae” was published by Rakuyodo, who was the publisher for Yumeji’s books. Therefore it is believed that, behind the scenes, Yumeji provided support towards the publication of their magazine.

Reference

・“Takehisa Yumeji to sono shuhen” The Miyagi Museum of Art / The Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, 1988

・“Tsukuhae” NHK Plannet Kinki, 2014

・“Onchi Koshiro: Lyric and Modernism” The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo / The Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, 2016

Image captions

All images are from the collection of the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art. Reproduced from public domain images available on the Museum’s official website.

Image 1: ONCHI Koshiro “Lyric: Leap” 1915, woodcut on paper, 13.4 x 9.8 cm (published in “Tsukuhae” VI on 5 May 1915)

Image 2: ONCHI Koshiro “Lyric I” (partial image) 1914, woodcut on paper, 13.3 x 11.0 cm (published in “Tsukuhae” I on 18 September 1914)

Image 3: ONCHI Koshiro “Wish of Idiot” (partial image) 1914, woodcut on paper, 8.6cm x 5.8cm (published in “Tsukuhae” III on 16 December 1914)

Image 4: ONCHI Koshiro “Things across the Sky” (partial image) 1914, woodcut on paper, 13.6cm x 11.0cm (in the collection of “Tsukuhae” III, published on 16 December 1914)

Image 5: ONCHI Koshiro “Lyric: Enlightening Moment” (partial image) 1915, woodcut on paper, 13.5 x 9.6 cm (published in “Tsukuhae” V on 7 March 1915)